“Just a few months ahead of the trip, we did a preparation journey around Northern Europe and we chose to come to the UK.

We expected the weather to be challenging and wanted to navigate some storms in preparation for our around-the-world trip. Fortunately for us, we ended up having the best weather and we got to indulge in the Dorset coastline both on the ground and also in the air in our sustainable DA50 RG aircraft.

Image by: Diamondo

One of the stops was in Bournemouth where we did a COVID test and then went out to try the local specialty fish and chips. The best thing about that plate was that it is actually sustainable.

Sustainable aviation fuel book & claim that we support is currently based on used cooking oil as a feedstock for fuel production; oil which has been used in deep fryers, for example, to fry our crispy fish and chips.

After being used in the kitchen, that oil is collected by companies and brought to refineries where it is processed into sustainable aviation fuel and other fuels which can be used for different machinery. This is how I was able to help produce some cooking oil that can be used in aviation later.”

This is a story told by Matthias Niederhäuser, an aviation consultant and one of the two Diamondo pilots, along with Robin Wenger, both of whom completed a full circle around the globe in over 111 days, covering 58,000 kilometers and taking up 217 hours of flying time. Diamondo Earth-rounding links and supports various initiatives that accelerate the aviation industry’s transition to a more sustainable one. The across-the-world travels highlight widely accessible technology, emphasising the potential to create and withstand this sustainability.

Image by: Matthias Niederhäuser

World population is not likely to be able to produce the amount of cooking oil needed to power the global aviation industry with SAF, but this solution can have quite an impact.

“Our stops in the UK were because of the initiatives there. In Chester, close to Liverpool, was one of the airports which had physical sustainable aviation fuel available to us, so we fueled up the plane with sustainable aviation fuel,” said Niederhäuser.

The main goal of SAF is not to bring additional carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. There is no single sustainable aviation fuel, it’s rather a broad description of many different fuel types. What these all have in common, is that no additional carbon dioxide is created during production – unless additional energy is needed which is when some carbon dioxide is produced.

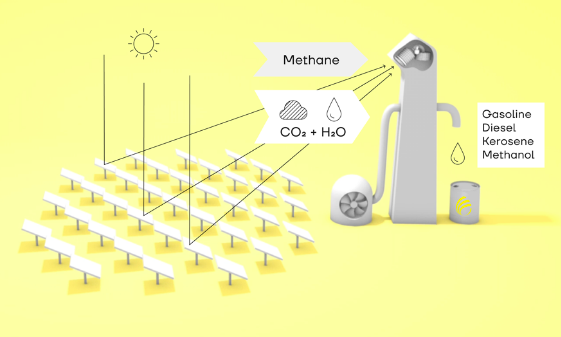

SAF are produced by turning sun into fuel. Mixing carbon dioxide, water, and methane by using solar energy produces syngas which in turn is processed into any type of fuel using the sun-to-liquid technology.

SAF are paramount in achieving carbon dioxide emission reduction. There are tons of projects on electrifying aviation and hydrogen projects of aircraft that directly run on hydrogen. The entire development cycle certification and testing cycle within aviation would take ages before worldwide fleets of airliners are replaced.

This is why aviation is needed in solutions that operate within the current infrastructure. The current aircraft and engine technologies is why SAF are so important. They provide a solution that can be implemented now.

During the around-the-world flight, Diamondo managed to use and support sustainable aviation fuels even when they were physically out of reach.

“It’s called the book and claim system and works quite similarly to compensaid by placing an order for sustainable aviation fuel, then claiming the carbon reducing credits; we are not the recipients of the fuel, but we paid for SAF to be fueled into a different aircraft, which travels through an airport where sustainable aviation fuels are delivered”, said Niederhäuser.

Compensaid is a platform initiated by Lufthansa, but can also be used for flights on any airline as a tool to offset carbon dioxide and make travel more sustainable. It provides a carbon dioxide calculator for each flight, allowing users to discover their options for a greener experience by deploying SAF and contributing to high quality climate projects to compensate for the unavoidable emissions of that flight.

People can also try to reduce emissions by investing a bit into SAF. Niederhäuser explained that being conscious about flying is important, as “it does not come for free for our planet. It’s convenient to fly but a lot of energy is also being used up. Compared to pre-pandemic prices, one can fly to Spain for 30 pounds, yet so many people are not willing to invest in an extra 5 or 10 pounds to compensate for emissions.”

This is how everyone can contribute to making flying more sustainable, even if that happens one litre at a time.

“Even if that comes down to just adding one extra litre of SAF into the system, that creates a demand and incentivises fuel producers to upscale their production,” said Niederhäuser.

“Making a stop, and seeing what is being done at the university I attended, made me really realise that sustainability is getting more of a spotlight. I think that’s a good development. It gives me hope that sustainability in aviation, which is so important in the industry, is being taught at the university level now.

Doing what we do best as pilots is basically flying planes from A to B. Being able to do it from A to B and not back to A, but after B you can fly to C and to D and make your way around the world and back. I felt enormously privileged that we were able to do so. I get goosebumps thinking back at it now.

We were able to carry out such a mission for what we believe is a noble cause and lived the experience as pilots to fly to places we would dream about as kids. Having such a young team supporting us and being able to do it successfully on schedule makes us proud, but also makes us realise that it is a once-in-a-lifetime experience.

I really hope that the people we spoke to about investing more when flying are convinced to invest in sustainable solutions, and do so voluntarily. I believe that we managed to do that throughout Diamondo, but many more need to follow. And that’s why we keep on doing what we do best,” said Niederhäuser.

Niederhäuser mentioned the team doing an exceptional job in pulling off the preparations and the flawless execution of this flight around the world. Here is what project manager Alexander El Khawaja had to say.

Global initiatives aiming for sustainable aviation include projects that remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, reduce fuel burning through clean technologies, use solar power plants instead of fossil energy, promote making air travel carbon dioxide neutral, and build fuel-efficient aircrafts.

Diamondo Earth-rounding managed to reduce carbon emissions by around 80% compared to fossil fuels, which is quite impressive, but it’s not 100%. This is why this project aimed at compensating for the remaining 20% by investing in climate protection initiatives and promoting green aviation and sustainable solutions.

The broad and most common solution to making flights greener is operational efficiency: flying from A to B in a more efficient manner, requiring less fuel burning and reducing the carbon footprint across the flight itinerary drawn out.

There are also airports which are developing to become more efficient in supplementary areas including ground infrastructure like diesel powered cars or push back tractors which tow the aircraft back and forth that are replaced by electric vehicles.

SAF are among the initiatives having an even larger positive effect in helping aviation become carbon-neutral because they use fuel that is no longer being produced from fossil sources. SAF use up carbon that is already either in the atmosphere or in the existing carbon cycle without extracting new fossil carbon and expelling it into the atmosphere.

Every location favours a distinct solution to make aviation greener. This has a lot to do with the resources available in abundance and that can be used to create the energy needed to make flying greener.

Solar energy is available in abundance in places like Dubai, so renewable energy there is most logically produced by the sun.

Diamondo’s flight over the North Sea, from Cranfield to Amsterdam, overflew wind parks in which a lot of wind energy was being produced. So, in the UK, it makes more sense to power sustainable fuel production with wind energy rather than with solar energy.

Niederhäuser is based in Switzerland and is deploying a scheme for private pilots for flight schools and aviators who do not consume sufficient fuel on their own. Because of that, they don’t have the bargaining power to get a batch of sustainable aviation fuel from suppliers.

Collaborating with the Swiss government and a number of universities, Niederhäuser is creating a platform where orders for sustainable aviation fuels SAF are aggregated, where fuel companies purchase the SAF. Subsequently, Niederhäuser provides paperwork certificates to the private pilots who are willing to pay and invest their time and money.

And with all the hard work done by Niederhäuser and his team, the hope will be that other pilots follow suit in tackling climate change.