Only half of the 90-odd student course representatives showed up for the election. The venue was sticky and hot thanks to the closed windows on a surprisingly sunny day and many people in the room just seemed to want it over with.

The course representatives of Bournemouth University (BU), who stood scattered around the room, were in charge of day-to-day university business and collecting survey feedback. They would have to vote for six school representatives.

These are the folks who represent students at the highest levels of university governance — at the School Academic Board and the Education Council of Students’ Union of Bournemouth University (SUBU).

They would work on changes to academic programmes and negotiate with the university vice-chancellor for the budget of the Media School. An important job, in other words. But the voting procedure for these six positions, it turned out, was surprisingly lax.

There was no secret ballot.

Don’t get me wrong, the overall student representation model of BU is one of the best in the country and was recently decorated with an award by the Quality Assurance Agency for higher education (QAA). But a lack of democratic standards at its very foundation is more than just a cosmetic flaw:

It is like a shiny skyscraper built on brittle bricks.

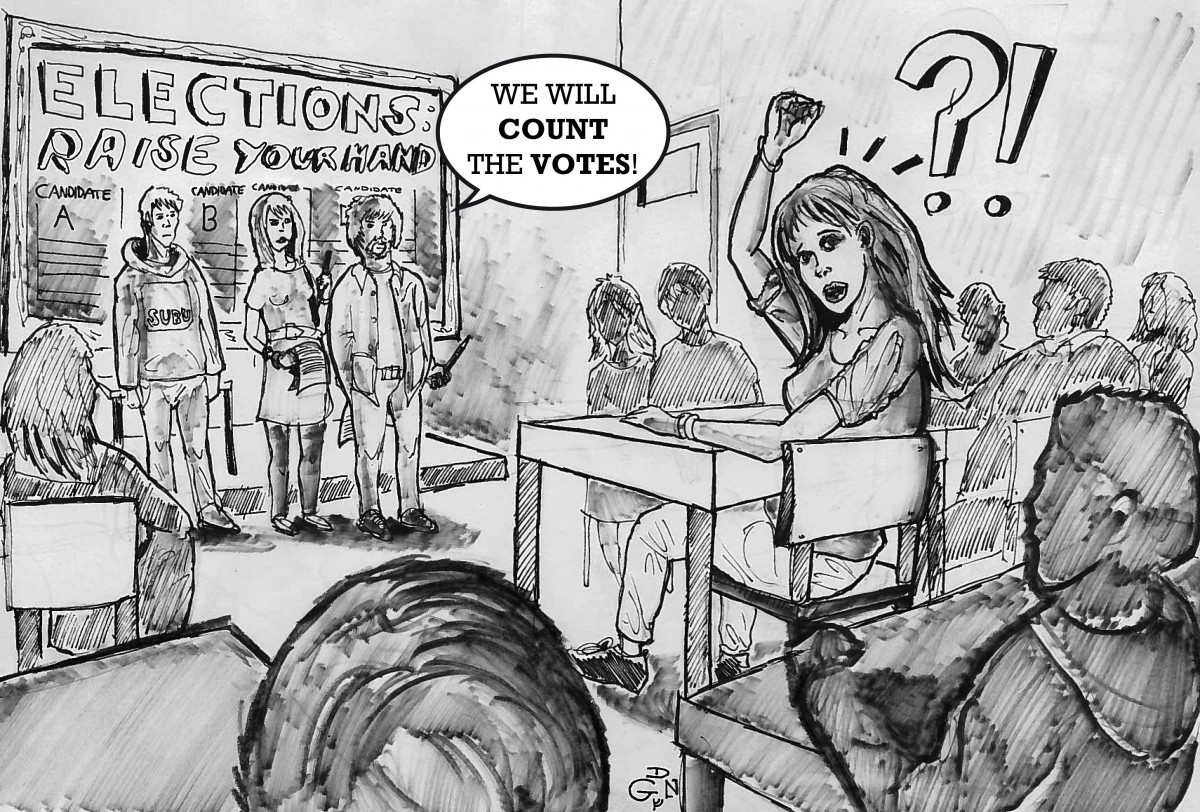

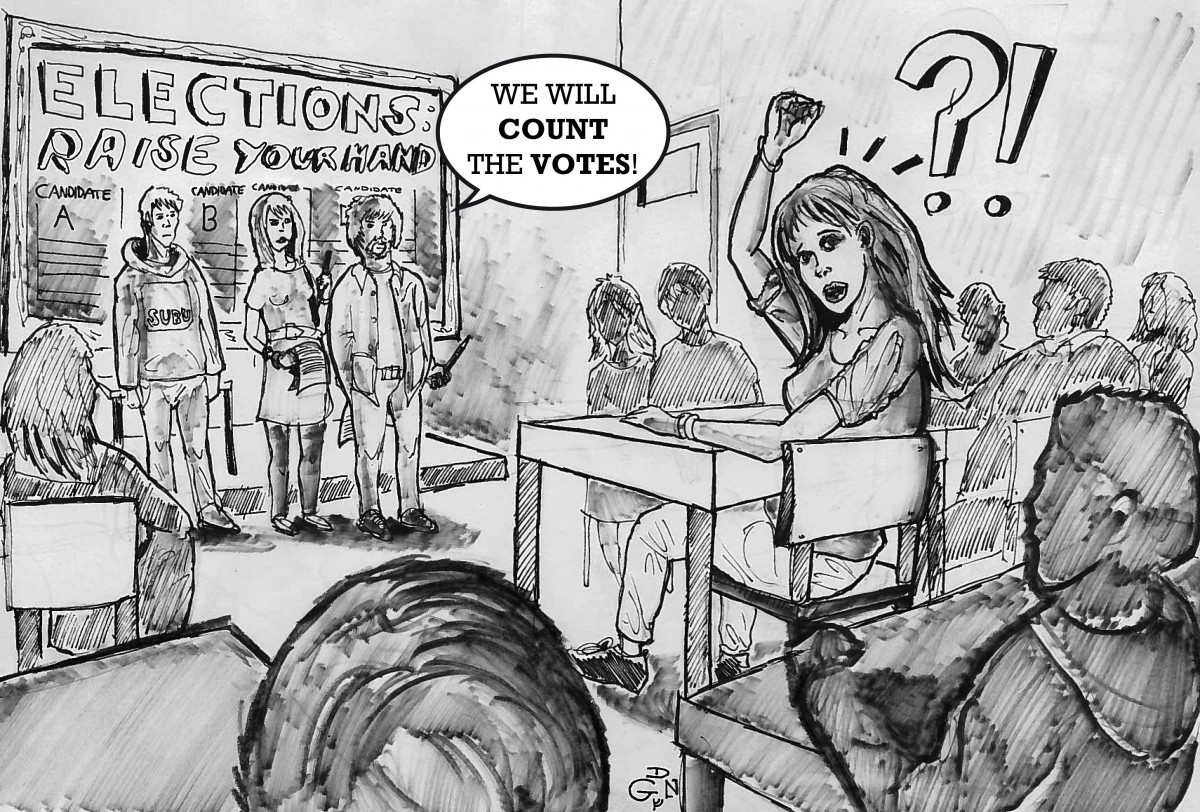

So there we were, 40-odd student reps seeking to vote on the six prestigious positions, divided into five frameworks according to our study programmes. Between two to five candidates per framework would put themselves forward, speak a few words, leave the room and be voted on by a simple show of hands.

As the name of the first candidate was called, a female student rep raised her arm. She looked around and lowered it again.

One vote, or rather half a vote, for Candidate A.

In 1974 a political scientist described the very effect I had just witnessed. Her name is Elisabeth Noelle-Neumann and the name of her theory is the Spiral of silence.

The model describes how people who find their own opinion to be in minority behave. It holds that these people would not openly voice their opinion, but remain silent, or even conform to the opinion of the majority against their own beliefs.

No one wants to be the social caterpillar in a room full of butterflies.

Back in the classroom as the second candidate was called to vote for, I suggested a simple secret ballot on a piece of paper so no one would be influenced by the decisions of their peers.

The somewhat cheeky response and “fix” for the issue from SUBU Education VP John Gusman: “Everybody, just close your eyes.”

By the time the votes of Candidate C were counted, it became clear that counting two votes for one candidate takes significantly less time than counting 15 for another.

“Everybody, just close your eyes” –VP Education John Gusman

Again, I said this was not a fair way of doing things. But the election continued. The winners were to be announced later.

I asked Gusman why the SUBU chose not to go for a secret ballot. He said:

“We like this type of election because it is the most authentic one and is definitely in line with standard democratic procedure. I saw that everyone did close their eyes and I am confident that no one was influenced by the time it took to count the votes.

“We have carried out over 850 elections by this nature and have never witnessed any issues with it.”

Interestingly, the elections for 40 positions on the student councils of SUBU – about 10 more positions than the total for school reps – were carried out at the same time by secret ballot.

Why the double standards? Gusman said it would involve too much bureaucratic paperwork.

Just one month earlier it was not too much work, though. For the election of the lower ranked student representatives – carried out by academic staff – at least we were offered a secret ballot.

As I said, apart from the highly motivated candidates, many people in the room just seemed to want the election over with.

As funny as chance sometimes plays out in life, the next day I stumbled into a talk organised by the BU Politics Society on ‘Public opinion, polling and politics’. The lecture was from social research agency Ipsos Mori’s Deputy Head of Political Research, Tom Mludzinski.

I asked Mludzinski if a voter is likely to be influenced by knowing what the majority votes for. Would that change how that person votes?

His answer: “Yes, personally, I’d like polling to be banned during elections because it can indeed have an effect on voters’ decisions, as was the case in the 1997 Labour landslide win of Tony Blair. ”

Later he’d also say that “elections always should be secret and anonymous, as people tend to agree with the opinion of their peers and should not be embarrassed to make an independent voting decision”.

Then I met Alison Smith, treasurer of BU’s Politics Society, a second-year BA Media and Politics student and 35-year-old mother of two.

“Even at the school of my kids they use this very basic principle of a secret ballot to vote their representatives” – BU Politics Society treasurer Alison Smith

“What’s your take on school reps being elected with a simple show-of-hands with the instruction to simply ‘close your eyes’?” I asked.

“I am surprised, shocked and appalled. I don’t even know what to say,” she replied. “A secret ballot should be the obvious thing to do. Especially for this fundamental level of university governance – these are the people who negotiate with the vice-chancellor.”

She added: “Even at the school of my kids they use this very basic principle of a secret ballot to vote their representatives.”

From the experience of the student rep election it becomes apparent why a secret ballot is not only good practice, but also necessary. Students from some courses felt that the open election disrupted their class spirit. Some would ask fellow students to vote for them as friends. Others would just sacrifice the young friendship bonds to classmates to the prospect of becoming a student rep.

All of this would easily be avoided by a secret ballot, allowing for every voter to make their cross for the person he or she sees fit – be it your friend, or someone “not on your-wave-length” but the most mature and proficient candidate.

Gusman also defended himself by stating that following the election no one said they were unsatisfied with the voting procedure.

True, I did not voice my concerns again and no one else seemed to openly care. Maybe I also precautionarily not only closed my eyes but also covered my ears and thus did not hear Gusman ask if everyone was satisfied.

But the fact that one student rep, myself, twice found the election process not to be fair while it was taking place should have directly led to a secret ballot – if Gusman had wished to be in accordance with the democratic standards to which he so repeatedly referred in his justification.

A fair election is one in which every single voter can make a decision “in all conscience” for the candidate that seems the most suitable. And that is why in an election of any type and level of governance the word “fair” is almost exclusively paired with the word “secret”.

Never have I seen ‘fair’ paired with ‘lazy’ so far.

An election that is perceived as unfair leads to further disengagement with politics, which especially in an university like BU that offers solely one study programme in politics, is more than troublesome. It would be the job of the organisers of the election to inspire engagement by making everyone feel comfortable to vote.

Democracy is about going that extra mile. It’s not all fun and feedback surveys.

Full Disclosure:

I am the student representative for the MA Multi-Media Journalism course at BU and was elected by withdrawal of candidacy of fellow students. I did not put myself forward as a BU school rep candidate as I lack the time and experience for such an important and labour-intensive position.