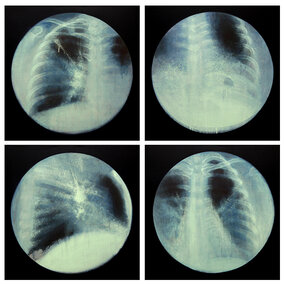

As a graduate of the prestigious Moscow State Academic Art Institute and a promising young painter from Russia, Paulina Siniatkina had her entire life and career ahead of her when she got a shocking diagnosis of tuberculosis.

“I didn’t know what kind of disease it is, and what will be the consequences… I saw my mother’s tears, and this was terrifying…,” the 31-year-old artist recalled.

Paulina is just one of an average ten million people diagnosed with tuberculosis every year. Although it remains one of the world’s most deadly infectious diseases, it has largely been brought under control in recent decades through established diagnosis, treatment and prevention measures. However, the spread of coronavirus, in poorer countries particularly, has raised a concern amongst experts that this progress could soon be undone.

The former President of the European Respiratory Society, Tobias Welte, said setbacks in diagnostics, treatment, and control of the disease will inevitably increase cases and multi-drug-resistant tuberculosis. “We were on a good track; however, I’m afraid, and I have a lot of concerns that this is coming down now,” he added. “We will see this (an increase) immediately after the corona pandemic ends.”

The Stop TB Partnership based in Geneva states that the COVID-19 response seriously diminished tuberculosis outreach and services, leading to a drop of around 20% in diagnosis and treatment worldwide. The international NGO, which has been fighting tuberculosis globally for over twenty years, claims that 12 months of COVID-19 eliminated 12 years of progress in the global fight against tuberculosis.

“It is a clear step back because, mainly in the low-income countries, the care programs for tuberculosis collapsed,” the German pneumonologist Welte corroborated. “To come back into what had been built during the last decade will be a huge effort. “

Impact of tuberculosis on society

Although curable, tuberculosis (TB) is the infectious disease that leads to the most deaths worldwide, even ahead of HIV, according to the World Health Organisation (WHO). Around 1.4 million people died of tuberculosis in 2019, and around 10 million were newly diagnosed in the same year, including around 1.2 million children. Over 5 000 women, men and children still die each day from TB.

The disease is not equally distributed worldwide. 30 countries accounted for 87% of new TB cases in 2019, with 8 countries accounting for two-thirds of the total. India, Indonesia, China, the Philippines, Pakistan, Nigeria, Bangladesh and South Africa make up the top ten.

Top 10 countries (TB deaths) in 2019 in red.

Obstacles in the prevention and treatment of tuberculosis

There is currently no vaccine against tuberculosis, apart from an old Bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) vaccine, which is not very effective and has several side effects, the director of the Clinic for Pneumology at the Hannover Medical School Welte said. For this reason, vaccination programmes have been stopped in countries with low tuberculosis incidents.

One of the major problems of effective tuberculosis treatment is multi-drug resistance (MDR) due to non-standardised treatment, Welte explained. Treatment of tuberculosis is a long and costly process lasting up to six months and requiring a combination of four different drugs.

Factors like multiple side effects, monotherapy, and stopping treatment prematurely are MDR tuberculosis’s main drivers. This is often the case in the Asian, South African, and South-East European countries, Prof. Welte added.

Highly stigmatised

The doctor in the Russian hospital who treated Paulina Siniatkina warned her not to tell anyone about her disease; otherwise, she “will be branded for life.” The young woman’s first impression about her condition was: “This is a disease which I have to keep silent about.”

Despite the presence of the “fatal cough” plague in many parts of the world and extensive knowledge about its course and treatment, tuberculosis patients still grapple with prejudices and stigmatisation. Even in countries with a high incidence rate, such as in eastern Europe or India, conception of it as a “social” disease of the homeless and drug addicts is pervasive and entrenched.

During the course of the treatment, Paulina experienced marginalisation in all areas, amongst medical and government workers and even patients themselves.

“If there were no stigma, everything would be much easier,” she said.

Female tuberculosis survivors especially seem to suffer from stigmatisation. Numerous revelations of women about their stigmatisation experiences related to the disease abound on social media platforms like Twitter or Facebook. A recently-founded international network of women, TB Women, defined as its mission to “build a coordinated movement for a gender transformative TB response” and reduce the marginalisation of the affected through women’s empowerment and policy advocacy and knowledge sharing.

A life-changing disease

For Paulina Siniatkina, encountering tuberculosis has turned the life of the young artist upside down. It helped her realise many things, move to a healthier lifestyle, and find her personal mission and purpose in art and life.

As a tuberculosis survivor and a co-founder of the first international network of people with tuberculosis experience TB people, she is now a tireless crusader for the destigmatisation of the disease and the afflicted. “I’m just doing my job, and my job is to make everybody understand that no one is safe from TB; it can affect anyone…We are all equal,” she explained.

The disease and desire to remove taboos from it have become a big source of inspiration for her artwork exhibited in numerous collections worldwide, including Bill and Melinda Gates Medical Research Institute in Boston. “It’s a traumatising experience, of course, but… I’m actually…grateful to this experience,” the young artist said.