Alice Jackson had been in university for just a few months when she started comfort eating.

“I didn’t really click that well with anyone. I was living in horrible accommodation and I just felt lonely,” she recalls.

After a sudden weight gain, she decided to go on a diet and became increasingly obsessed with exercising, rituals and meal preparation. When her father was diagnosed with cancer several months later, she began to feel like she didn’t want to eat at all. “When I look back on it, I realise now that I was pretty depressed. But I didn’t really know any better then. I was young and I didn’t understand what was going on with my body.”

By the time she went home for the summer, Alice’s parents were horrified at how much weight she had lost. They urged her to seek help.

By chance, she noticed a flyer for SWEDA (Somerset and Wessex Eating Disorders Association) on the toilet door at Bournemouth University and went to one of their meetings where she was told to visit her GP. She was eventually referred to cognitive behavioural therapy at Poole Hospital, and was set specific weight gain targets which helped her to gradually ease into a healthy diet again. By the end of her second year, she was discharged from therapy.

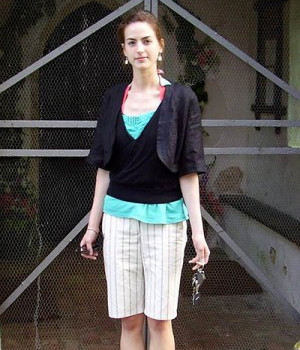

Alice is now fully recovered and leads a normal life, living in London and working in digital marketing. Although symptoms develop before the age of 16 most cases (62%), her experience of developing an eating disorder at university is not an unusual one.

Jess Griffiths, founder of Bournemouth charity I-Eat (now called Restored), says that students can be particularly vulnerable to developing eating disorders. “If there’s an insecurity around identity, coupled with having to cook, that can sometimes trigger off an eating disorder,” she says. “You don’t have as much money to live on, and therefore that narrows your [food] choices as well.”

New research from PwC for the charity B-EAT indicates that the cost of eating disorders to the economy is around £15 bn, in large part due to sufferers receiving help too late and needing to be admitted to hospital for their condition.

“Once it’s become patterns of rigid behaviour, it’s harder to undo. Research shows that the sooner you spot it, the more chance there is of recovery,” says Jess Griffiths. She thinks the most important thing is getting family involved at an early stage to help prevent the eating disorder from spiraling out of control.

Eating disorder charity B-EAT says there is too much variation across the country, including among different universities, in terms of access to treatment. “Some universities have a very robust support network for students with eating disorders and others not quite so comprehensive,” says B-EAT spokesperson Mary George. “Many students experience difficulty in accessing treatment quickly enough in the transition between the family GP and student health.”