Darkness descends in Bahrain and the drivers take their positions beside their cars. The racetrack is bustling but underrepresented. In the sea of white faces stands one black man, arguably the face of the sport, Lewis Hamilton. Hamilton hops into his silver Mercedes, overseen by his white mechanics, overlooked by his white team principal and spoke to by his white race coordinator. As the track clears and the lights go out, Hamilton single-handedly flies the flag for ethnic minorities.

The Englishman is the first and only black driver in the history of Formula1 and he has been vocal about his desire to inspire a young generation of black drivers: “I want to see the sport that gave a shy, working-class black kid from Stevenage so much opportunity become as diverse as the complex and multicultural world we live in”. Hamilton aims to make Formula1 more open to people who aren’t from the traditional moneyed elite.

The lack of racial diversity isn’t just in Formula1, it is evident across all of motorsport

The lack of racial diversity isn’t just in Formula1, it is evident across all of motorsport. Hamilton remains the only black man even when you include the lower tiers of professional driving, like Formula2, Formula3 and FormulaE. That equates to just 1.2% of drivers being black. The trend continues across to MotoGP, the pinnacle of motorcycle racing, too. None of the MotoGP, Moto2 or Moto3 riders are from black backgrounds.

For a discipline that spans across five continents and features international drivers, riders and crew, it is yet to host a grand-prix in Africa in the 21st century. F1 psychologist, Jide Joseph thinks: “it’s got to do with the economics and the class, because when you think of motor sports and motor activities, you think of the middle-east, the south of France and very expensive areas where ethnics and black people are not around and didn’t grow up”. The last grand-prix to be held in Africa was the South African GP in 1993. There were talks of the race returning to Kyalami but the CEO of motorsport South Africa, Adrian Shultz said the main obstacle was the cost of hosting.

The absence of racial diversity on racetracks is more complex than motorsport being institutionally racist. Instead, the issue stems from the cost of karting with the average beginner kart costing upwards of £1000 (not to mention the additional costs like racing gear and lessons). The cost continues to rise as drivers progress through the ranks and a more competitive kart is a ‘necessity’.

Although Formula1 regards itself as a meritocracy, it can’t be that in reality

The expense of karting is unfeasible for black and ethnic minorities of which 69% have a weekly income under £800 according to GOV.UK. Additionally, The Guardian found in 2019/20 that 53% of black families live in poverty. This issue extends beyond racing, this is a socio-economic issue that plagues modern-day society. Black families are massively underrepresented in sectors that could afford to fund their child’s motorsport ambitions. Although Formula1 regards itself as a meritocracy, it can’t be that in reality. For example, in the 2021/2022 season, two drivers – Lance Stroll and Nikita Mazepin were gifted their seats by their billionaire fathers. The former is the son of Aston Martin team owner Lawrence whilst the latter is the son of Dmitry Mazepin, the primary financer for Haas F1. This begs the question; in motorsport, does money outweigh talent? The sport will never truly realise the potential of young drivers while the expenses of getting involved remain unfeasible for the majority of the population.

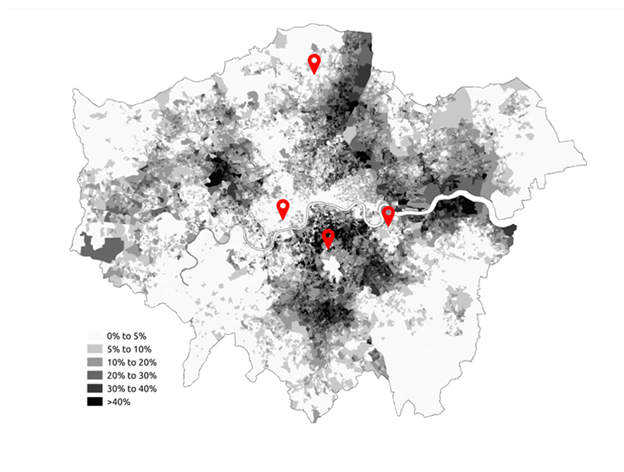

Low levels of black participation in youth karting can also be linked to karting schools being inaccessible for black communities as they are typically based in more affluent areas. For example in London, the most racially diverse city in the UK, the majority of karting schools are located in boroughs where Black people are at a minority of under 20%, such as Enfield, Acton and Charlton.

However, Formula1 are trying to address the racial disparity in the sport with the ‘diversity and inclusion’ scheme, in which they write: “We are exploring ways to make karting more affordable and accessible”.

Sam Green from Rye House Karting suggests: “I think the best way to do it is a scholarship style racing scheme because that is the main hurdle for everybody really, the cost involved. Irrespective of what background they come from, it’s an expensive sport to get into and it’s an expensive sport to compete at a high level. So, I think more funded drives would be excellent for those drivers who can’t necessarily afford to get involved”.

“Better funding for STEM subjects in schools will lead to a wider and more diverse pit crew”

Sam also touched on the lack of support given to STEM subjects (science, technology, engineering and maths) in schools noting: “Equally I think more funding towards education as a lot of motorsports come down to the engineers and obviously better funding for STEM subjects in schools will lead to a wider and more diverse pit crew, designers and engineers as well which is always a good thing”.

This aligns with Formula1’s incentive to offer more opportunities to people from underrepresented backgrounds. In a press release F1 wrote “we look to reduce the financial burden on students and their families, Formula 1 will commit to financially supporting a number of engineering scholars from diverse backgrounds at a range of universities in the UK and Europe”.

Jide supports this initiative saying: “when it comes to other things around the sport like engineering science, computing and mechanical engineering, I’m sure there’s young kids out there that would love to work in the paddock and be naturally good at it”.