Across the UK, women are rolling up their sleeves on a big mission: to save the planet.

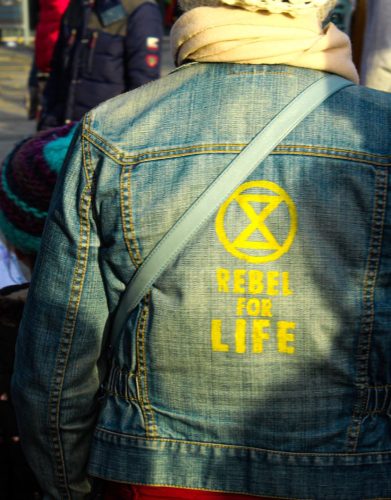

From the grassroots up, British women are leading the way on environmental action. Some are hitting the streets as protestors involved in bold and brave direct action – pressing the nose of the apathetic British establishment to the glass and forcing them to confront the horror of a rapidly-approaching future. Research conducted by Aston University shows that more women were present at Extinction Rebellion’s 2019 demonstrations than men.

But they are also thousands of unsung heroines, quietly going out their day, choosing to make sustainable and eco-friendly choices. They’re swapping out plastic water bottles for disposable cups, cycling to work rather than driving, and even making sweeping lifestyle changes such as becoming ‘flight-free’ and forgoing meat.

As women lead the charge, and men are falling behind: at least, according to the research.

Mintel, a global market research firm, claims that women in the UK are more eco-friendly than men. Whilst only 59% of men were willing to make a commitment to ethical living, 71% of women were. The Global Future think-tank found similar findings for the UK: 40% of female respondents in their study claim to have altered their eating habits to help fight climate change (compared to 27% of male respondents), and 34% of female correspondents also altered clothing and fashionable purchasing habits compared to 16% of male respondents.

If this eco-gender gap is real, it begs the question: where are all the men? And why are women – proudly, but unfairly – shouldering the fate of planet earth on their shoulders?

Joanna Bury, a lawyer, writer and climate activist from Dorset, has been aware of the pressing danger of climate change and the ecological emergency since she was a girl. But this concern blossomed in 2019 after stumbling across Extinction Rebellion and their hourglass symbol online.

“I mean the moment I saw it, I thought that’s what’s needed – because this is so grave and so profound.”

Bury quickly joined an Extinction Rebellion group and later set up her own in Wimborne, a small town in Dorset, focused on both wider and local environmental issues. One of the Wimborne group’s most memorable direct action involves donning bright flamingo-pink hazmat suits to protest Wessex Water’s pumping of raw sewage into the local river, the Stour.

“I think the way I look at [climate activism] is I try and think how to communicate with the public and how to get the message across and I believe very much in taking action on the streets,” Bury says. “We have a thing in our group that we try to have more actions than we have meetings.” She sees her work and the work of climate emergency activists like Extinction Rebellion – particularly female activists – as the latest saga in a proud, empowering lineage of female change-makers: “There is a wonderful history of activism. Take the suffragettes, for example, how they literally changed history. They are an enduring example for us all.”

Although Bury doesn’t believe the experience of men and women in climate movement is necessarily different, she does believe that more women are involved in activism at the community level. She explains that in XR Wimborne, there are generally more women. “I have given this some thought and I think maybe it’s to do with women’s position in society. You know women are traditionally very nurturing and look after families and have always been concerned with issues of life and death. And sadly, historically women have been subjugated, and I think perhaps this has given us more empathy. I mean certainly in regards to the planet, for me it breaks my heart when I think of nature being destroyed.”

Could gendered norms be responsible for the eco-gender gap? Even in the 21st century, women are still responsible for the domestic and household sphere. In 2019, a new survey looking at household chores and gender led by Professor Anne McMunn at University College London found that women do more housework than men in 93% of British households. Consequently, according to The Women’s Environmental Network (a charity founded by women in 1988 to promote the female perspective and voice in the climate movement), women also find themselves overwhelmingly responsible for consumer decisions – 80%, in fact – including making the decision on sustainable swaps: shopping at charity shops, reducing meat consumption on the food shop, or choosing a greener supplier for the home.

But it’s important to stress that the possibility of an eco-gender gap, in terms of women making more sustainable or lower-carbon lifestyle changes than men, is not as straightforward, clear-cut or black-and-white as it might first appear.

Dr Rachel Howell, a lecturer in Sociology and Sustainable Development at the University of Edinburgh, said: “Recent research has suggested that men have higher carbon footprints than women because men eat more meat, and men do more leisure activities involving travel. But whether that is necessarily to do with women deliberately acting in a eco-friendly way is a different question. For example, are women travelling less for leisure because they want to cut their carbon footprint or is it because women are less likely to drive or own a car?”

Howell points out that there is an issue with what the eco-gender gap is measuring. “There are quite a few environmentally-friendly behaviours that people don’t think about because it’s often not about buying stuff but avoiding other behaviours. For example, if men are using already-owned rucksacks or sports bags to carry their shopping, that’s arguably more environmentally-friendly than buying a new reusable shopping bag.”

Women do express more concern about certain environmental issues, they express more worry, and they express more willingness to make certain kinds of choices. Howell says this difference could be down to different levels of trust towards institutions. “Women express less of a trust institutions than men. They have less of a belief that the government and businesses are going to sort the problem out. Meanwhile, certainly for white middle-class men, the status quo has worked out quite well for them.”

“We can take putting responsibility onto individuals too far, we’re not going to solve the climate change issue through individual voluntary behaviour. We need large-scale societal change. However, I think there’s a value in individuals changing their behaviour because it promotes a change in social norms – every person who changes their behaviour in a more sustainable way makes that behaviour seem more normal – and social norms shape our behaviour to a level we don’t recognize. Also, if individuals show they are willing for necessary changes to affect them, it potentially gives people a stronger position from which to call on policymakers and businesses to make changes.”

This grassroots change, responsibility, however, lays a heavier burden of guilt and time on women compared to men. The Spring 2015 Global Attitudes survey by the Pew Research Center found that in 11 developed countries – including the UK – women are more likely to be concerned that global climate change will harm them. Joanna Bury experiences this: “I think the difference between knowing [about climate change and feeling is huge, I feel it emotionally and psychologically – the danger that we’re in.”

Caroline Hickman, a lecturer at the University of Bath and practicing climate psychologist, explains that eco-anxiety is unique in that it’s not just about environmental problems, it’s the anxiety that it is caused by not acting to reduce the harm being caused. At the mild end of the scale, it doesn’t affect daily functions. It’s a general pressure about doing the right thing to save the planet. But the problem lies at the severe end where eco-anxiety can result in a nihilism, a ‘what’s the point’ and ‘there’s no future’ ethos to life, a real helplessness and hopelessness.

But Hickman isn’t convinced that eco-anxiety impacts women to a larger extent. “Younger men are just as concerned,” she says, “but are less likely to talk about what they feel. Whereas younger women generally grow up expressing their feelings as a normal part of everyday life, men are trained to hide their feelings. I suspect they feel similarly but are not as confident at sharing it, so it might look like more woman are worried even though men are to equal amount.”

And is eco-anxiety a bad thing?

Certainly at the extreme end of the spectrum, but Hickman wants to reframe the conversation: eco-anxiety, when managed, can be a driver for eco-conscious choices and change. She says: “I don’t want people to get rid of it, I want people to understand it. You only feel eco-anxiety because you care, and you should be proud of feeling eco-anxiety because it’s a measure that you care about the planet.”

Whilst the eco-gender gap does exist, and men need to pick up their share of the burden, it’s important to acknowledge – as Hickman points out – that British women’s climate activism is something to be proud of.

Joanna Bury agrees: “But you see, that’s the thing about taking action. That’s the thing about even just going out to the street and handing out leaflets and having really nice, friendly conversations with the public. It’s a wonderful outlet for all this rage and anxiety. It really is a wonderful outlet. I can’t tell you enough. I mean, I don’t spend my whole time feeling depressed, angry, anxious… far from it, I am actually quite an optimistic and positive person, and I just love to talk to the public and try and spread the light.”